Rendering and Re-Rendering in React

In this article, you will learn what happens behind a 're-render' in React, what causes them, how to avoid them, and patterns to consider for optimizing our applications.

Introduction

Understanding the key concepts of a library is essential to feel comfortable working with it. That’s why I decided to write this article about the cornerstone that gave rise to React: ‘renders’. Although React has evolved significantly in recent months, its essence remains intact: creating component-based interfaces that return JSX.

Mastering the process of ‘rendering’ and the events that trigger it is crucial for designing efficient applications and building a solid foundation for continued improvement. At the end of the day, working with React always leads us to discuss ‘renders’, so why not understand them thoroughly from the start?

What is a ‘Render’ in React

Let’s start by understanding what ‘render’ means in React. Essentially, a ‘render’ is the process by which React sends the JSX returned by a component to the DOM. This JSX is calculated from three key elements:

- The properties (props) that the component receives.

- The component’s internal state.

- The values of the contexts that the component consumes through the Context API.

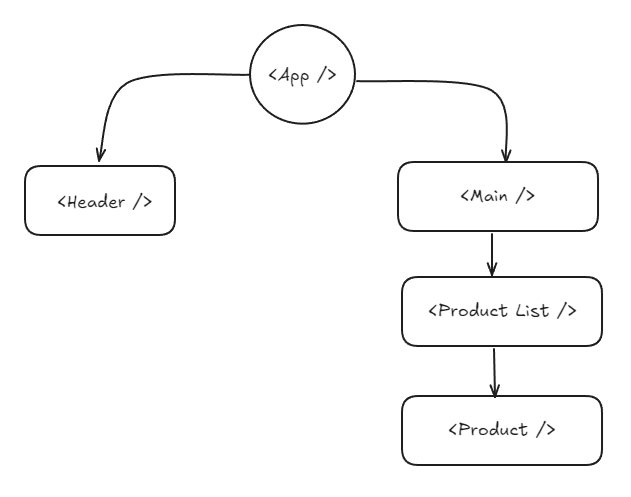

A component is rendered whenever it is part of the component tree we have defined.

When the browser loads our application for the first time, React generates a component tree. Each component returns pieces of JSX that, when combined, define the complete structure of the interface. However, this structure is not static. As the user interacts with the application, the component tree can change in various ways:

- Adding new components.

- Removing existing components.

- Modifying the state or props of already present components.

The key moment in this process is the ‘initial render’, which occurs when a component first appears in the tree. During this first render, the component sets the initial values of its state.

From there, we enter the realm of ‘rerenders’, where things get really interesting.

What are ‘Re-renders’

A ‘re-render’ is any rendering of a component that is already in the DOM and does not correspond to the ‘initial render’.

Re-renders occur when there is a change in the application state, caused by:

- User actions, such as interacting with an element of the interface.

- External updates, such as the arrival of data from an API via a fetch call.

Types of ‘Re-renders’

We can classify re-renders into two main categories:

- Necessary re-renders: These are renders where the component is directly affected by a change, and its new JSX will differ from the previous one. Example: In a counter, when the user presses the button to increment it, the component needs a new render to display the updated value.

- Unnecessary re-renders: These occur when a component re-renders even if it has not been affected by the change and generates the same JSX as in the previous render.

Common cause: An inefficient structure or poor planning of our application.

Unnecessary re-renders can affect the performance of the application, so identifying and avoiding them is key to maintaining a smooth user experience.

Reasons a Component Re-renders

A component can re-render for one of the following reasons:

- Change in internal state (declared using useState), usually as a result of a user action, such as clicking a button.

- Change in context, if the component is consuming a context and its value is updated.

- Re-render of the parent component, which causes, by default, all child components to re-render.

Let’s take a closer look at these:

Changes in State

When we declare a piece of state within a component using the useState hook, any change in that state, triggered by invoking setState, will cause a re-render of the component.

export const Counter = () => {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

return (

<div>

<p>Count: {count}</p>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}>Increment</button>

</div>

);

};Note: Each time the state is updated with setCount, the component is rendered again.

Change in Context

When the value of a context changes, all components that are consuming that context via the useContext hook will re-render to ensure the view reflects the update.

const ContContext = createContext(0);

function App() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

return (

<ContContext.Provider value={count}>

<Counter />

</ContContext.Provider>

);

}Note: When the count state changes, the context in the Provider receives a new value. As a result, all components using useContext(ContContext) detect this change and automatically re-render.

Re-rendering the Parent Component

By default, a child component will re-render whenever its parent component does. In other words, when a component re-renders, all of its child components also re-render, even if there are no direct changes to them.

function App() {

return (

<div>

<Component />

</div>

);

}

function Component() {

...

}Note: In this case, the Component component re-renders every time the App component does.

How to Prevent Unnecessary Re-renders

Now that we know the reasons a component can render, let’s explore some techniques that will help us prevent unnecessary re-renders and optimize the performance of our applications.

Place State as Low as Possible

This technique is useful when working with complex components that manage multiple states, especially if some of them are only used in specific parts of the component tree.

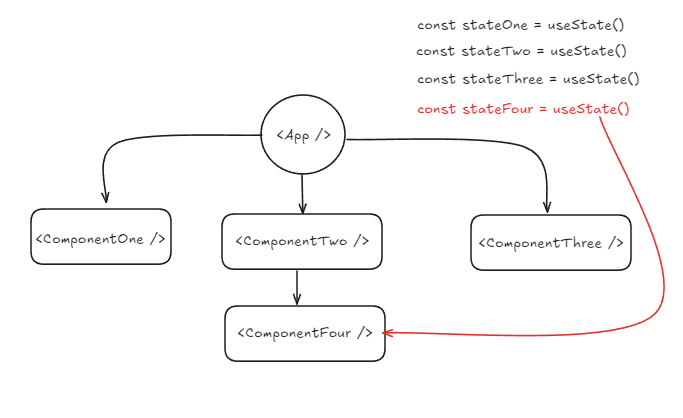

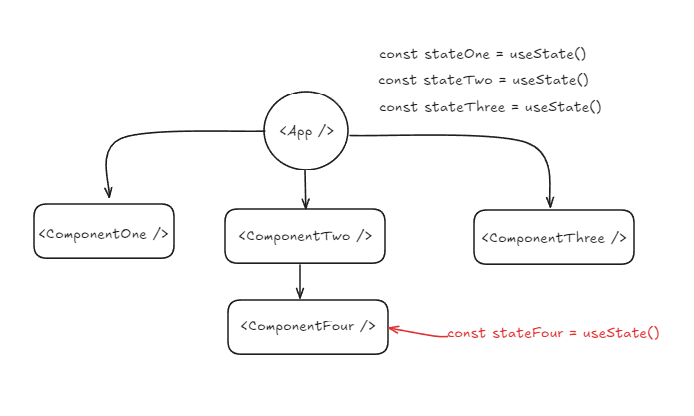

For example, if stateFour is only relevant for ComponentFour, keeping it at a higher level will cause any change in this state to trigger a render of the entire tree (remember: rendering a parent component also re-renders all its children). This can be inefficient.

To avoid this issue, we can define stateFour directly in ComponentFour, limiting its impact and ensuring changes only affect the component that truly needs it.

Pass Components as Props

This technique is especially useful when working with expensive-to-render components that are contained within a component that renders frequently, such as a form managing inputs.

const FormComponent = () => {

// Component logic and state

return (

<div>

<input type="text" placeholder="Input 1" />

<input type="text" placeholder="Input 2" />

<SlowComponent />

</div>

);

};Every time FormComponent renders, the inputs and SlowComponent also re-render, which can negatively affect performance.

To avoid this problem, we can pass the expensive component as a prop, for example, using children. This works because children is just a reference to the component, and React does not re-render it unless it explicitly changes. It’s as if the component is already ‘pre-rendered’.

const ParentComponent = () => {

return (

<FormComponent>

<SlowComponent />

</FormComponent>

);

};

const FormComponent = ({ children }) => {

return (

<div>

<input type="text" placeholder="Input 1" />

<input type="text" placeholder="Input 2" />

{children}

</div>

);

};This technique, known as ‘wrapping state around children’, is very useful for optimizing similar cases.

Note: This approach is not limited to the children prop: we can define any number of props in a component and use this pattern to prevent unnecessary renders.

Avoid Creating Components Inside Others

It is important to avoid an anti-pattern that can cause significant performance issues: defining a component inside another.

function SomeComponent() {

const OtherComponent = () => {

const [state, setState] = useState();

useEffect(() => {

// Effect logic

}, []);

return <div>Component content</div>;

};

return (

<div>

<OtherComponent />

</div>

);

}This code includes the OtherComponent component defined inside SomeComponent, which is an anti-pattern in React because it causes OtherComponent to re-mount and execute all its effects every time SomeComponent renders. This can be inefficient and lead to performance problems.

Memoize components with React.memo

React’s memo function allows us to optimize functional components by wrapping them to avoid unnecessary renders. If the component’s props haven’t changed since the previous render, React reuses the previous result, improving performance. For those who have worked with class components, memo behaves similarly to the shouldComponentUpdate function, which allowed you to decide if a component should update. Let’s see how to use memo with some practical examples.

Component without properties

In this case, the component we are wrapping with React.memo does not receive any props. As a result, this component will not re-render even when the parent component renders, as it doesn’t depend on external data.

This makes the optimization even simpler, as we don’t need to check if the props have changed since there are no props to check.

const NoPropsComponent = React.memo(() => {

console.log("Rendering NoPropsComponent");

return <div>This component has no props</div>;

});

const ParentComponent = () => {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

return (

<div>

<button onClick={() => setCount((prevCount) => prevCount + 1)}>

Increment

</button>

<NoPropsComponent />

</div>

);

};Note: In this example, every time ParentComponent renders (e.g., when count is incremented), NoPropsComponent does not re-render since it has no props and its rendering does not depend on any change in the parent component’s state.

Component with properties

When a memoized component with React.memo receives props, it will only re-render if one of those props changes. If the props don’t change between renders, React will avoid unnecessary re-renders, which can improve performance.

const ExpensiveComponent = React.memo(({ value }) => {

console.log("Rendering ExpensiveComponent");

return <div>The value is: {value}</div>;

});

const ParentComponent = () => {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

const [value, setValue] = useState("initial value");

return (

<div>

<button onClick={() => setCount((prevCount) => prevCount + 1)}>

Increment

</button>

<button

onClick={() =>

setValue((prevValue) =>

prevValue === "initial value" ? "new value" : "initial value"

)

}

>

Change value

</button>

<ExpensiveComponent value={value} />

</div>

);

};Note: In this example, ExpensiveComponent will only re-render if the value of

valuechanges. Even if thecountstate in ParentComponent changes (when the first button is clicked), ExpensiveComponent will not re-render ifvaluedoes not change.

Combine useMemo / useCallback with memo

In React, memo is a powerful tool to avoid unnecessary renders of a component, but what happens when the component’s props are functions, objects, or arrays? In these cases, memo won’t work as expected unless we use the appropriate hooks. Let’s see how we can improve this.

When we pass functions or objects as props to a memoized component, if those values change on every render, memoization won’t take effect. This is because React treats the new functions or objects as different values, even if the content is the same. Let’s see this in some examples.

import { memo } from "react";

const Child = ({ onClick }) => <button onClick={onClick}>Click me</button>;

const MemorizedChild = memo(Child);

const Parent = () => {

const handleClick = () => console.log("Clicked!");

return (

<div>

<MemorizedChild onClick={handleClick} />

</div>

);

};In this example, the Parent component creates a new handleClick function on every render. Although the function logic is the same, React creates a new reference every time, which causes MemorizedChild to receive a new value for onClick and re-render unnecessarily.

Another common case is when we pass an object as a prop. Let’s see the following example.

import { memo } from "react";

const Child = ({ pet }) => <div>{pet.name}</div>;

const MemorizedChild = memo(Child);

const Parent = () => {

const pet = { name: "Fido" };

return (

<div>

<MemorizedChild pet={pet} />

</div>

);

};In this case, Parent creates a new pet object on every render. Although the object’s content doesn’t change, its reference does, causing MemorizedChild to receive a new object on every render and re-render unnecessarily.

Fortunately, React provides the useMemo and useCallback hooks to prevent creating new instances of objects and functions on every render. Let’s see how we can improve these examples.

The useMemo hook memoizes a calculated value between renders and only recalculates it if its dependencies change. It takes two parameters:

- A function that returns the value to be memoized.

- An array of dependencies, similar to the

useEffecthook. The function will only execute if the dependencies change.

On the other hand, useCallback memoizes functions in the same way. It takes two parameters:

- The function to be memoized.

- An array of dependencies. If any of the dependencies change, the function is recalculated; otherwise, the same instance is reused.

import { useMemo, useCallback } from "react";

const ParentComponent = ({ name }) => {

const pet = useMemo(() => ({ name }), [name]);

const logName = useCallback(() => {

console.log(name);

}, [name]);

return <div>...</div>;

};With this, the previous examples can be improved to avoid unnecessary renders. Let’s see how to apply useMemo and useCallback to improve the examples.

For the onClick function case, we can memoize it with useCallback, ensuring that its reference never changes between renders.

import { memo, useCallback } from "react";

const Child = ({ onClick }) => <button onClick={onClick}>Press</button>;

const MemorizedChild = memo(Child);

const Parent = () => {

const handleClick = useCallback(() => {

console.log("Clicked");

}, []);

return <MemorizedChild onClick={handleClick} />;

};Now, even if Parent re-renders, handleClick will not be recreated because useCallback memoizes the function.

Conclusions

With this article, we have covered various React techniques to avoid unnecessary renders, which can significantly improve the performance of your applications.

My advice is to first familiarize yourself with the different causes that can trigger a re-render and learn to identify which components are susceptible to optimization. With the approaches I have explained, you will be able to make your application more efficient while also gaining a better understanding of how React’s rendering system works.

Mastering these techniques will not only allow you to write more efficient code but also deepen your understanding of how React handles UI updates and rendering, which is key to building fast, high-performance applications.